The rooflines of the ’50s and ’60s are possibly the most defining feature of midcentury architecture. They re-cast what a suburban street could look like and turned a normal family home into a work of art. While façades and well-landscaped front yards finish the picture, the signature angles (or bold rejections of them) demand your attention right from the curb. Join us as we dive deep into the architectural history of the era’s most iconic rooflines.

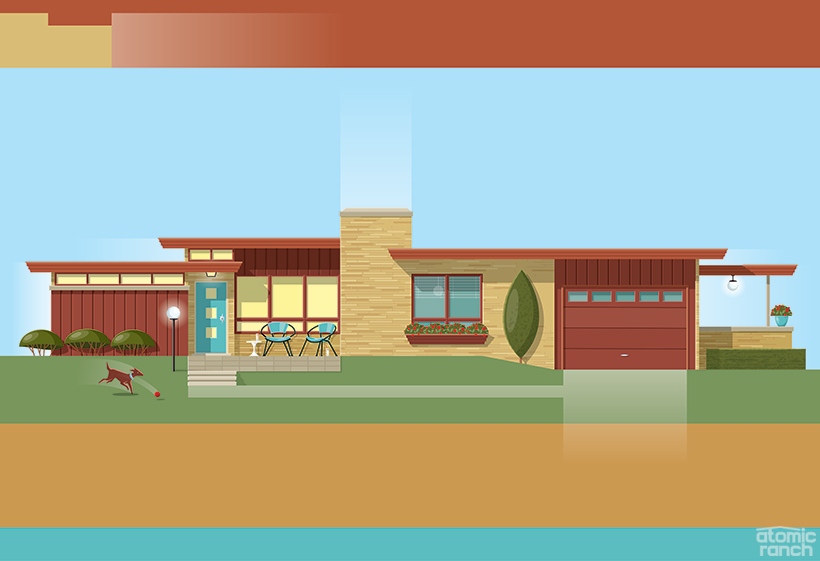

Low Slung

Perhaps the most common of the rooflines seen on midcentury homes, the low-slung roofline conveys a clear message of retro charm. Ranches across the United States don this low-profile roofline—also referred to as a ranch roof or shallow pitch—making it as attainable as it is desirable. With predecessors of Victorian and Craftsman lineage, the minimalistic front elevation is a clear breakaway from the ornate styling of Edwardian-inspired homes and the bulk of artisan-crafted bungalows. The simplified roof breaks away from the multiple rooflines of the previous eras and instead offers undeniable character via typically flat facades. Eye-catching accents of color as well as texture provided by stones or brick bring these classic homes to life with charming curb appeal. The roofline was first popularized in the 1920s, but it truly took the nation by storm with the boom of suburban life that followed WWII.

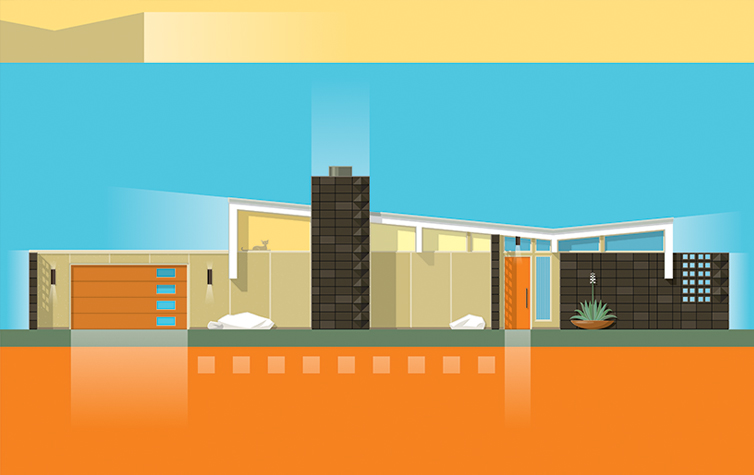

Flat

It’s the roofline that inspires, confuses and concerns—the flat roof. Without a pitch in sight, the flat roof is one of the defining elements of midcentury architecture. Even though their sleek silhouette goes hand in hand with the clean lines of all things mid-mod, the first era of the flat-topped roof was not the midcentury. This simple roofline can be traced back to medieval architecture, but it had its first brush with stateside popularity during the Arts and Crafts movement, thanks to the Spanish bungalow. With a sleek façade and simple styling, the mid-mod flat roof is a modern rebel. Despite their appearance of perfect parallel to their lot, flat roofs do indeed come with a tilt. This ever-so-slight angle is nearly impossible to note from a street view, but it is vital to ensuring proper runoff and drainage—as are proper waterproofing materials. Even with these elements in place, the flat roof is a viable option only in areas where runoff is of secondary concern.

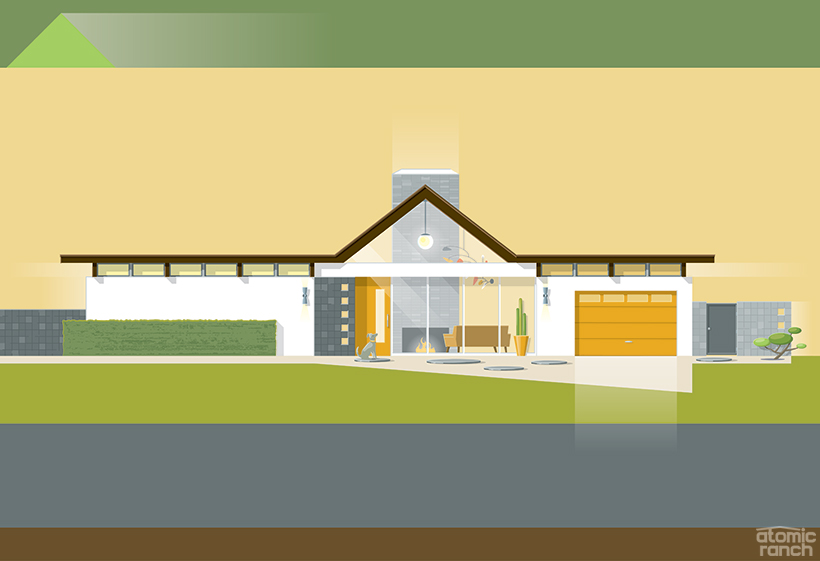

A-Frame

Along the beaches of Sagaponack, New York, the A-frame-style home first saw its resurrection from basic utilitarian buildings and off of snowy mountainsides to become an icon of midcentury creativity. When architect Andrew Geller designed the purely A-framed Reese House and it graced the pages of The New York Times in 1957, it secured itself as a staple of mid-mod design. The stunning look soon found its way inland, but with a groundbreaking floor plan that centered the “A” and extended the flat-roofed rest of the house to either side. Famed California architect Joseph Eichler used the A-frame as an opportunity to bring the outside in—setting the pitch over a courtyard at the center of the home or creating a deep, plant-filled entrance that feels like an interior entryway.

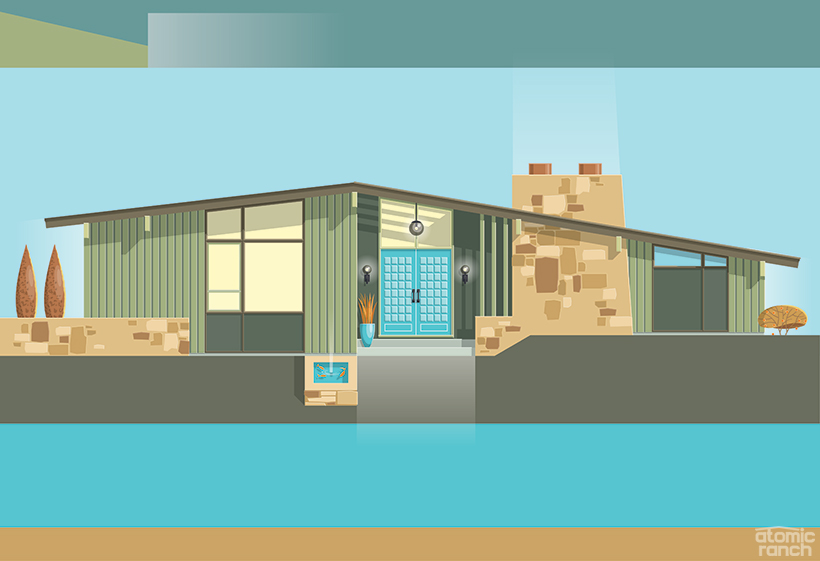

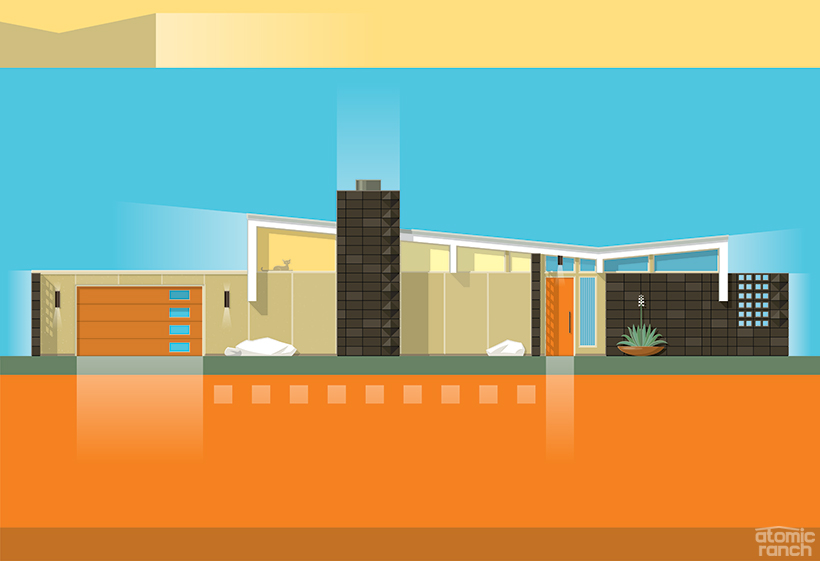

Butterfly

An artistic representation of the modernist spirit, the butterfly roof appears as the wings of its namesake bug mid-flight. The butterfly roof is simple in its beauty and functionality. It is as if the low-slung roof was pressed down at its apex, tipping the usually downward-angled roof up towards the sky. Aside from offering incredible mid-mod curb appeal, this inverted style creates space for windows set high along the roofline. The unusual placement allows copious amounts of natural light into the house without compromising on the privacy of its dwellers. While many credit architect William Krisel with the creation of the butterfly roof, his credit belongs only to bringing the design to the masses through his 1957 neighborhood in Palm Springs, Calif. The first sketch and planned butterfly roof was designed by architect Le Corbusier in 1930. That project never took flight, and architect Antonin Raymond created a similar home to Le Corbusier’s design in Japan. Marcel Breuer was then inspired and built the Geller House in Long Island, New York, in 1945.