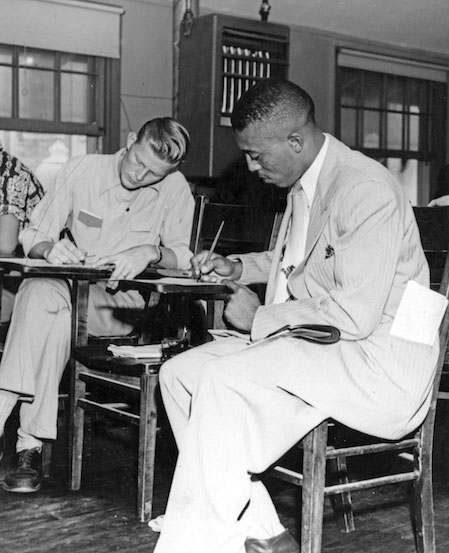

Why are there so few Black Mid Century Modern architects? Well for one, it was difficult for Black students to even gain access to the schools where they could pursue their goals of entering the trade. Modernist architect John Chase is one such example. There’s a long list of “firsts” that precede his name. Chase enrolled into the University of Texas at Austin in 1950, he was first Black student to do so at any of the major Southern colleges. His enrollment came just two days after the U.S. Supreme Court voted to desegregate the UT graduate school, and reporters were on hand to document the event.

“I remember, specifically, a photographer who talked non-stop to me about making history and getting the right moment on film,” The Houston Chronicle reports that Chase told a University of Texas magazine many years later. “He told me that I wasn’t officially accepted into the university until it became a contract, in other words, until the university took my money. He was right there next to me at that moment to snap the photo.”

Chase would go on to graduate having become the first Black president of the Texas Exes, a UT alumni club and became the first licensed black architect in the state of Texas (in fact he remained the only one a whole decade following).

When none of the predominantly white firms in the state would hire him after graduating, he opened his own firm in Houston. The rest of his career he would continue not only to break down barriers for his fellow men and women to follow, but he would champion and support persons of color in his field and his community.

John Chase’s Style

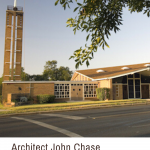

Inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian philosophy, Chase aimed to create communal unifying spaces. In fact, his Master’s thesis was “Progressive Architecture for the Negro Baptist Church.” It makes sense then that early in his professional career, he designed many Black churches such as the David Chapel Missionary Baptist church and the Olivet Baptist Church—both in Austin. These buildings emphasized open angular spaces that were minimal, bright and open. Their exteriors feature unique rooflines aimed at directing the eye to the towering crosses and steeples.

That penchant for bold style and angular form continues into his residential works. The Phillips house, his most famous, was built for the wife of Oscar L. Thompson, the first Black man to earn a degree from The University of Texas at Austin. The home features a distinctive green patterned roofline which dramatically hangs over expanses of floor-to-ceiling windows.

In 1963, Chase designed the Riverside National Bank, the first Black-owned bank in Texas. The building was a striking circular design with a long overhang roof and an adjacent serpentine pergola.

His Later Career

By the late 60s and 70s, Chase was working on large municipal projects such, George R. Brown Convention Center, the Harris County Astrodome renovation, and a commission to design the United States Embassy in Tunisia.

Chase also designed a number of projects for Texas Southern University campus in Houston, designing the Martin Luther King Jr. Humanities Building (1969), the Ernest S. Sterling Student Life Center (1976), and the Thurgood Marshall School of Law (1976).

Advocacy

John Chase broke barriers for his own education and career, but he didn’t stop there. He was the founder of the National Organization for Minority Architects, and the first Black man to serve on the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts. Serving that commission, Chase was the one to help choose Chinese architect Maya Lin to design the Vietnam Veterans Memorial at the National Mall in Washington, D.C. Throughout his career, she championed minority architects, engineers, and draftsmen not only in Texas but across the country.

Looking for more Texas modernism? Tour the home of modern home of Shea Ometz in Dallas or this renovation in Austin.

And of course, don’t forget to follow us on Instagram, Facebook and Pinterest for more Atomic Ranch articles and ideas!

1 comment