Breaking the mold of what “modern” was supposed to be, architect Paul Rudolph altered the landscape of Sarasota, Florida. His career would eventually lead him to create the Yale Arts & Architecture building, which is one of the earliest and best known examples of Brutalist architecture in the United States, but before this triumph there were what can affectionately be called “the Florida houses.”

Paul Rudolph: The Florida Houses by Christopher Domin and Joseph King preserves the tale of Paul’s work in the state. As Christopher and Joseph point out, “utopia” may have been Paul’s view of Sarasota—a place where his modernist designs could enhance the town’s perceived exotic aura.

Paul Rudolph: Early Years

Paul studied architecture at the Alabama Polytechnic Institute, now Auburn University. While studying, he saw Frank Lloyd Wright’s Rosenbaum residence, known as one of his finest Usonian houses, and the experience left a profound impression on Paul.

“Like Frank Lloyd Wright, Paul Rudolph possessed a rare ability to conceptualize architectural space, and he became a master of its handling,” Christopher and Joseph write. “Both architects had been trained as musicians in their early years, and their work can be thought of in such musical terms as rhythm and harmony, theme and variation, proportion, balance, and composition. There is a lyrical quality to their work, in the ways that they played the ebb and flow of space, enclosure and openness, movement and stasis. Each was acutely aware of spatial experience and the opportunity for beauty in composition.”

After completing his bachelor’s degree, Paul took a fateful job working for progressive architect Ralph Twitchell in Sarasota. The two worked together for six months before Paul entered the Harvard Graduate School of Design in the fall.

Establishing Credit

Following his service in World War II, Paul returned to work for Ralph. “Instead of staying in the northeastern urban centers like many of his contemporaries, he said later that he felt he could be ‘more effective with clients who were building second homes,’” Christopher and Joseph write. “‘There, for me, is something about modern architecture which makes it more sympathetic to warm climates than cool climates,’ he added.”

By 1950 Paul had his Florida architectural registration and Ralph’s firm had become Twitchell & Rudolph, Architects. As the firm grew, so did the town of Sarasota. “The community’s growing sophistication gradually made it possible for Sarasota to become, for a time, the setting for a highly innovative, modern, regional architecture,” Christopher and Joseph write.

Amid this idyllic setting, Paul and Ralph combined their talents to create homes that seamlessly merged design, technology and craft. “If Sarasota had its own Periclean Age, the period from the mid-1940s through the 1950s was that brief moment,” Christopher and Joseph write. SPACE WAS NOT AN EXPERIMENT for Paul and Ralph—it was their design principle.

Naturally Inspired

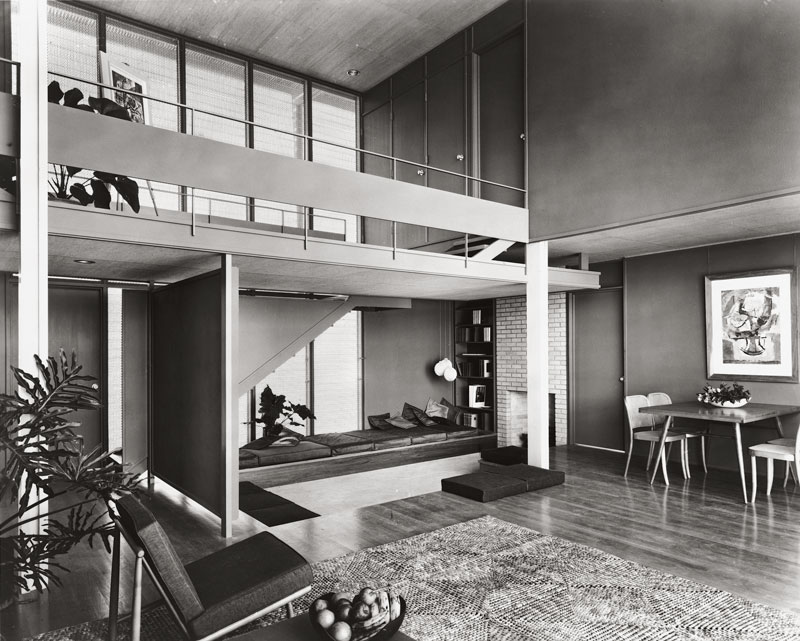

Paul’s designs often featured homes set low to the ground to mimic the relation of the ocean to the beach, ceiling-high windows and glass doors that open to views of palm trees, and living rooms with grass installed. And above all, Paul’s designs feature copious amounts of open space—a contradiction to a culture that relished privacy. Paul’s deep seated desire was that his designs felt bonded with nature.

With Paul’s focus on nature, some in his community may have viewed his and Ralph’s projects as the opposite of modern.

“They appeared not to participate in Saratosa’s ambitions of economic and physical development, and supposed growing sophistication,” Christopher and Joseph write.

Besides delving into Paul’s design philosophies, Christopher and Joseph share anecdotes about Paul, from his abhorrence towards photographers to how a lack of air conditioning could jeopardize his open-air designs. This all reveals Paul as more than just an architect who designed mold-breaking homes. Rather, readers are given the opportunity to look through the eyes of an architectural visionary who saw potential and possibility in a truly unique way.

Space as Decoration

The empty spaces in Paul Rudolph’s homes were not gaps he forgot to fill in, but not everyone understood this.

“Paul mastered his drawings to convey the sense of space in his designs, the most important aspect, which could easily just look like a lack of design,” Christopher and Joseph write.

For Paul, space was just as important as the building material—if not more. Thankfully, partner Ralph Twitchell agreed, believing that open space and natural elements outdo flashy décor.

“Now we do not ornament, we are in the new age—the age of air—and we use sunshine and color penetrating surfaces. It is not a new style but a new basic principle,” Ralph said.

Space was not an experiment for the two—it was their design principle.

Many were hesitant to jump on board Paul and Ralph’s architectural revolution. More space meant less privacy, and Paul threw around the term “goldfish bowl” to describe his projects. Despite this hesitation, Paul did not want the interior of his designs to be hidden from onlookers.

“The life of the house was intended to be observed as theater,” Paul said. Paul had an intention for every space in his designs, whether it was for design or theatrics.

The Umbrella House: Calculated Relaxation

Designed for Philip Hiss in 1953, Paul Rudolph’s Umbrella House looks like an elaborate sunshade that just so happens to have a house underneath. With a pool deck that takes up more length than the actual residence, the Umbrella House is a hybrid of tropical relaxation and modern design.

- Structure. The 17-foot parasol, combined with its adjacent two-story home, gives the Umbrella House a lofty effect reminiscent of a sumptuous seaside resort.

- Material. The framework of the house works hand-in-hand to reveal a connection to modern design and nature. The thin woodwork still shows that this is a work of minimalism, while the spaces in between allow sunlight to trickle through.

- Space. The generous amount of space permeating both the inside and outside of the Umbrella House serves two purposes. It appeals to Paul’s spacious view of modernism and offers uninterrupted views.

Looking for more architectural inspiration? Check out this post on the work of Al Beadle.

And of course, don’t forget to follow us on Instagram, Facebook and Pinterest for more Mid Century Modern inspiration!