“I needed to live in Orange County, which tends to have a dearth of interesting modern-era buildings [dating] from the mid-1930s to the mid-’60s,” says Brent Harris, 54, a financial executive. His first foray into renovating midcentury architecture was working with Marmol Radziner on the four-year intervention to save Richard Neutra’s Kaufmann House. Much has been published on that extensive 1990s home rehab, as well as the split with his former wife and rehab partner, and the subsequent $19 million Christie’s auction of the home that fell through. Today, Harris still owns the weekend property, which he now shares with wife Lisa Meulbroek, a college professor.

Harris was interested in architects A. Quincy Jones and Frederick Emmons’ work for Joseph Eichler, specifically in Fairhills, the last Eichler tract built in Orange, Calif., where the lots are relatively large and back up to low hills with borrowed views. Wanting to avoid paying for someone else’s shoddy improvements, he saw potential in a largely original, four-bedroom, two-bath model, despite substantial dry rot, termite-damaged beams, painted luan paneling, a cracked slab, half-usable plumbing and no A/C.

“I spent the first year studying what I had, interviewing contractors and other construction people about how they would approach such a project and whether they were interested,” he says. “I found neither satisfactory. I didn’t like how they would approach it and didn’t think that they cared or got it.”

Harris had worked with designer Brad Dunning on the Kaufmann pool house and another Palm Springs property, and he felt Dunning had a unique understanding of the period and how to bring that forward to today. The two discussed adding on to the Eichler.

“We considered an extension, but it was a smart move not to do that; the house is pretty perfect as it is,” Dunning says. “I have been lucky enough to work on restorations of Irving Gill, Wallace Neff, Cliff May and John Lautner homes, and a few by Richard Neutra, but this Eichler/Jones-Emmons of Brent’s might be my most detailed restoration/renovation ever.”

Conference calls between Harris, Dunning and technical design consultant Michael Johnston would typically start at 5:00 or 6:00 pm and often stretch past 10:00, as they focused on how to best achieve highly detailed originality. “For instance, on the sliding doors, the aluminum is almost impossible to restore, the rollers fail and they aren’t energy efficient, but the original Arcadia [models] are really tough,” explains Dunning. “Windows and doors make this house, and Brent and Lisa understand that. So we found someone to restore the doors and tracked down the correct handles and locking mechanisms. They get that, yes, the house would be more energy efficient and, yes, it would be easier if you pulled out all of the doors and windows. There are no better stewards for a house.”

“Brent wanted to bring the house back to what it was,” says Lisa Meulbroek, who grew up in a Mies van der Rohe–designed apartment building in Chicago. “Photos of [redone] Eichlers show that people have made different types of decisions about originality. Brent took the original kitchen cabinets and got several carpenters working on them so we could use and not replace them. Or the mahogany paneling that needed to be replaced: You can’t get the lowest or highest grade, it has to be the mid grade—things that I never would have thought about.”

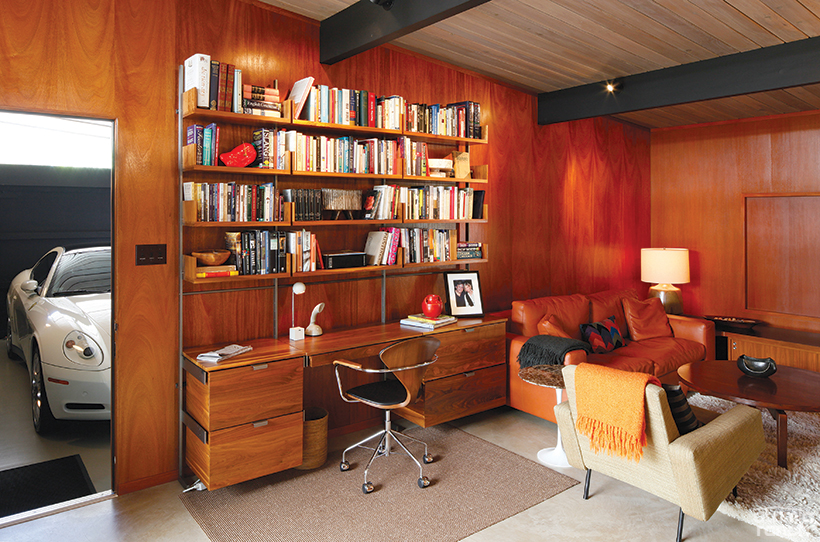

Harris is happy to expand on that paneling issue: “I reopened a sandstone quarry from the 1945 period to finish a piece of the Kaufmann [House] where the stone had been thrown away,” he recounts, adding that he also rejected said stone initially, but that’s another story. “In this case, I had to find luan mahogany of a mid grade. Today you can get low-grade mahogany that they use as shipping containers that has lots of knots—unacceptable. The higher grade is all perfect and bookmatched, all Arch Digest, and that’s wrong, so you have to find mid grade. Even then, you want to select the pieces.

“We didn’t want perfection for sure, but I didn’t want dereliction either, so it was interesting. The original luan is not super smooth, yet it’s not rough to your hand. So I specified that they not sand it down too much. Then, each panel took the stain differently—one would be yellow and one would be red.”

“From the restored burlap on the closet doors to the vintage phone from oldphones.com for the kitchen wall with the long cord in exactly the right color,” Meulbroek continues, “you go down the list and every single thing has been thought about, mulled over, discussed.”

“Burlap is the most low-cost material in the world, but we could not find the exact stuff [we wanted],” Dunning adds. “We ended up importing it from India from a place that makes potato sacks. I’m sure when Eichler and A. Quincy Jones were doing it, they just bought a million yards for a penny. That’s the thing about restoration—what was available at the time vs. what you can get at this moment.”

The renovation took five years, three of them involving heavy construction or extensive woodworking to restore or recreate damaged beams, exterior siding, cabinetry, paneling and millwork. Matching the original blue-gray color wash on the ceilings, selecting a paint palette, making 1964 fixtures and finishes functional again, and landscaping all took thousands of hours.

Air conditioning the house and adding storage and outdoor functionality were other priorities. “Brent and I were more involved with the restoration and the historical details; we look a little more at surfaces,” says Dunning. “Lisa was heavily involved with the hobby room, the kitchen and the bedrooms—she is way better at organizing these compact spaces. They’re almost like a yacht without one negative area of space not utilized.”

“I’m not sure [Eichlers] were easy to live in at the time,” Meulbroek comments. “The architects gave these houses a great look, but even for the day, I think the closets were probably small and probably had to be with so much glass and not that much wall space. They maximized the look, not the practicality.

“We thought hard about how we were going to make a house with four bedrooms work for a couple today,” she says. “We ended up keeping the master bedroom the same, while another is Brent’s office and [a third] given over to exercise equipment. Then we created a guest room with office space for me, too. We came up with a compromise that involves bunk beds, which took an incredible amount of time to design.”

While the radiant heat system just needed minor repairs, the absence of air conditioning was original but unacceptable. To avoid unsightly AC ducts on the roof, several split system units were installed with custom interior grills inset into the walls. Furnishings, artwork and accessories include midcentury and vintage pieces from Harris’ previous condo, items purchased expressly for this house under Dunning’s tutelage, and lots of books courtesy of Professor Meulbroek.

“I don’t like when you look at period houses and it looks like a complete time machine and re-creation of a Schulman photograph,” says designer Dunning. “There should be a basis of the correct style and period of the furniture, but you have to sprinkle in some contemporary and personal pieces. Brent is a real audiophile and he has some beautiful equipment; I just don’t like when it’s too precious. It’s a dance of looking at archival photos and the client’s personal needs.”

Asked to compare his two highly personal homes, Harris had this to say. “They’re both outstanding designs— both from the perspective of how history has judged them and as an occupant—and extremely dynamic in their looks. For modern structures, it’s a fine line, because they can be uncomfortable and cold, and that is simply not the case in either one of them. “Kaufmann, while not a large house, is a bigger house, particularly for 1946, and a much bigger property—close to 2.5 acres,” he continues.

“Kaufmann is a pretty spectacular masterpiece. But this [Eichler] is tremendous for what it was; I don’t know of a tract that is even close to this inspiration and realization. Fairhills was seen as a neighborhood with great design, while Kaufmann was conceived on a very high budget for an extremely important client.

“Our Eichler is a more functional, day-to-day house that forces some compromises on you—some of which are good. Get your act together and keep reasonable amounts of stuff.”

Harris and Dunning are confirmed serial renovators, but what about Meulbroek? I asked her if she never lived through another restoration, would that be more than OK? A pause, a laugh, then, “You have no idea…”