As the daughter of influential mid century artisan Harry Bertoia, Celia Bertoia feels that her role is to educate the public specifically about her father, and generally about the mid century era. According to Celia, most people are aware of Bertoia’s Diamond Chair, but many are unaware of his myriad other works—which include jewelry, sculpture, monotypes and sonambient recordings. Here, Celia shares about her journey to educate others, offering unique insight into the life and work of Harry Bertoia.

Questions and Answers About Harry Bertoia

Q: What inspired the start of the Harry Bertoia Foundation?

A: I’ve worn numerous hats in my life and never imagined I would be furthering the legacy of Harry Bertoia. As my husband and I looked at options for selling our business and changing our lifestyle, I realized that no one was truly carrying the torch. I made a statement to the universe that I wanted to take on that role, not having any idea how that would take shape. A month or so later, the universe began to answer.

A skiing buddy I hadn’t seen in 30 years invited me to do my first lecture. A psychic intuitive told me that the drawings on delicate paper from my father (monotypes) needed to be seen. Then, a gallery owner asked if I wanted to exhibit the Bertoia monotypes. It all began happening even before we sold the business. I knew that creating a foundation would be necessary to establish legitimacy and enable funding, so I went after it. I wrote up the application, and two years later we had a nonprofit.

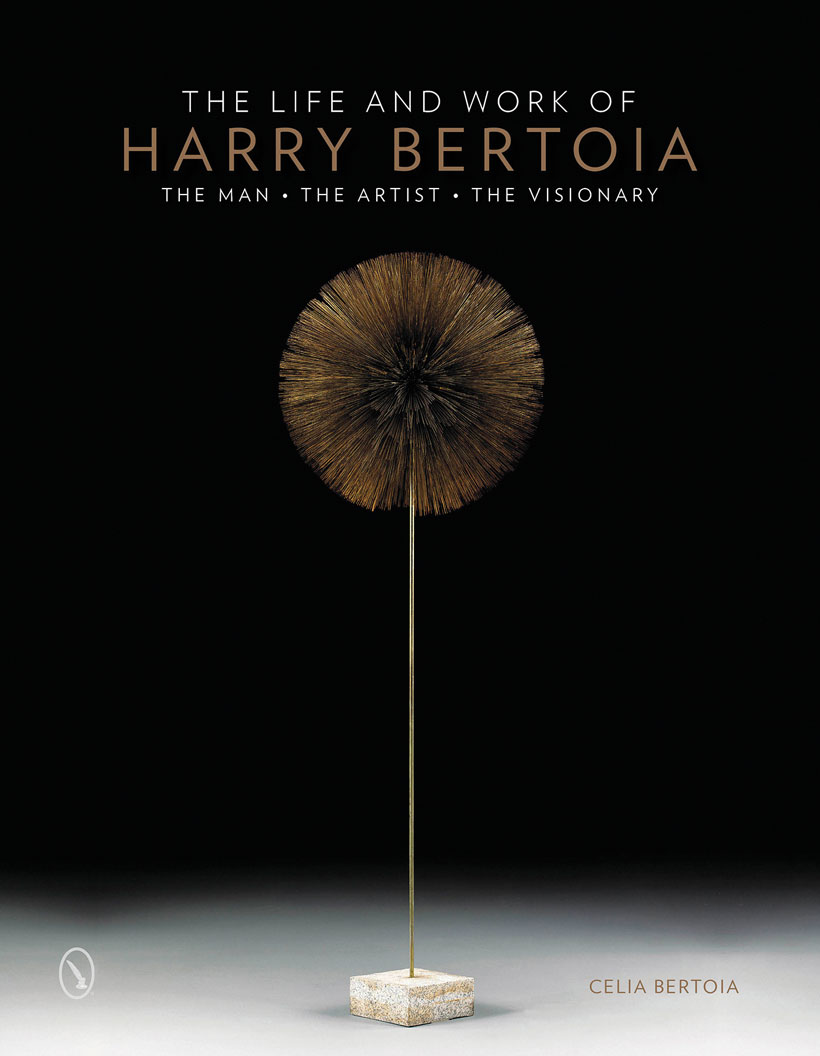

Q: What inspired you to write The Life and Work of Harry Bertoia: The Man, the Artist, the Visionary?

A: I am not an art scholar, although I’m learning, but I knew my dad. So many art books are just photos, dates and titles. There are several books like that already out on Bertoia, [but] my goal was to let people into my father’s world and discover what shaped his design and art. There are very few people who have the ability to help the reader get behind the scenes, and luckily my position as daughter encouraged that viewpoint. Plus, the book gave me the unexpected bonus of getting to know my father in a totally different way—from the perspective of architects, suppliers, coworkers and friends. He was a firm and strong father, but a generous and gentle friend.

Q: Do you have a favorite piece created by your father?

A: Yes, I do. After I had shifted my life direction to take on this legacy role, a woman phoned me out of the blue. She lived in my hometown of Bozeman, Montana, and had seen my name in the paper. Her voice told me she was older, and her words explained that she had taken a jewelry class from Harry Bertoia about 60 years ago at Cranbrook Academy of Art. We met and she showed me a silver ring that Harry had made as a sample of the lost wax process in class. Jayne gave me the ring, assuring me that she had worn it for many years and now it was time for it to go home to the family. As the ring met my finger, it fit perfectly and has been on my hand since that time.

Q: How did your father encourage you—and the rest of the Bertoia family for that matter—to express or respond to art and design?

A: Our home was full of art, music and design, that of Bertoia and many other artists. We were surrounded by the experience of art and design. It was such a normal part of life that we didn’t talk about it, but rather accepted and enjoyed it. My father never sat us down for an art history lesson, but would instead ask us what we thought about this painting or that sculpture or those chairs. He did that with everyone.

When someone pondering a sculpture asked Harry what it was or what it meant to Harry, he often answered with a question. “What does it mean to you? What do you see in it?” He rarely titled his work, partly to allow the viewer to choose his own significance. He taught us mostly by example and not words. But we were all encouraged to follow our own path, whatever that was, and we did.

Q: Have you drawn any lessons from his life and work that have shaped your own?

A: Oh my goodness, absolutely! My father was a very strong man, a relentlessly driven man, a man of passion, but a gentle, kind soul at the same time. Now that I have finally found my life work, I feel the [same] drive and focus that he demonstrated. Harry seldom used the word “impossible” but instead figured out a way to do whatever it was that he intended.

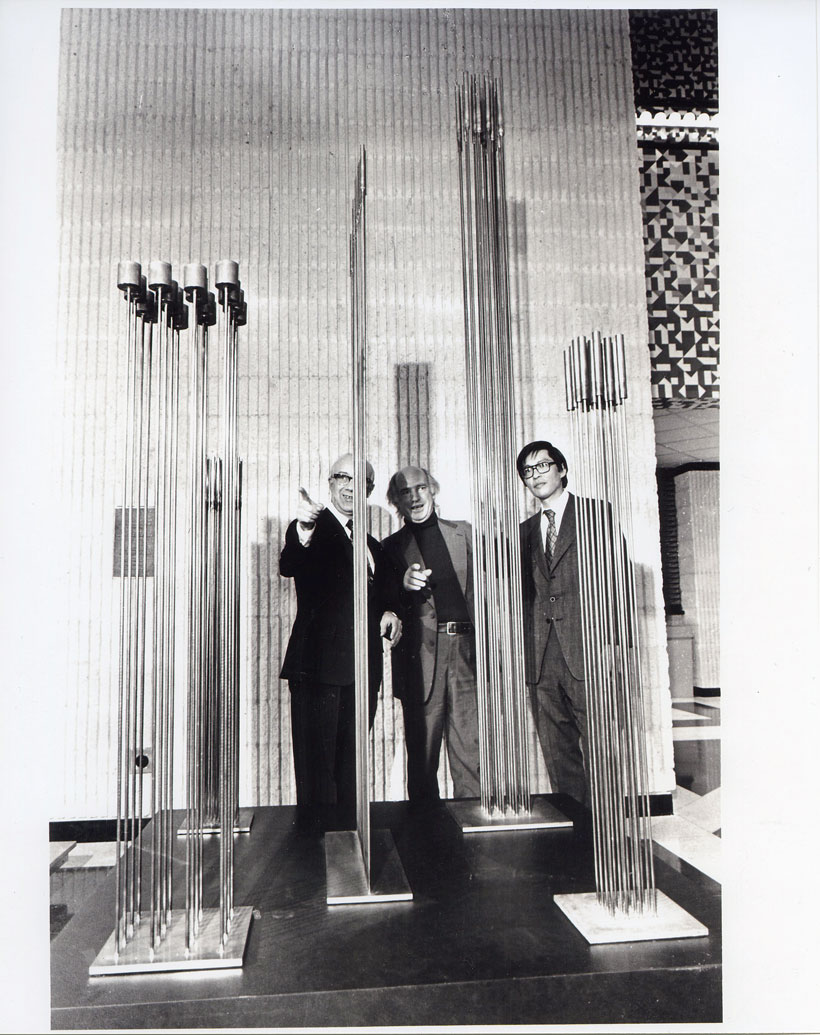

Sound & Sculpture

While working on bending a piece of wire for another sculpture, Harry accidentally pulled it too far—causing it to snap back against another wire and release a unique ping. In 1969 he had the perfect, acoustically balanced space to experiment in—a wooden barn on his Pennsylvania property. He then coined the term “sonambient,” defining it as “the sound environment created by tonal sculptures.”

These sculptures use touch to produce a unique sound environment. Many of the sculptures resemble large cattails due to their long thin rods and thicker tops set in even clusters. From the gallery in his barn to the sculptures installed at places like the Federal Reserve building in Richmond, Virginia and Ohio’s Bowling Green State University, the pieces beautifully combine sound and sculpture for a dimensional experience.

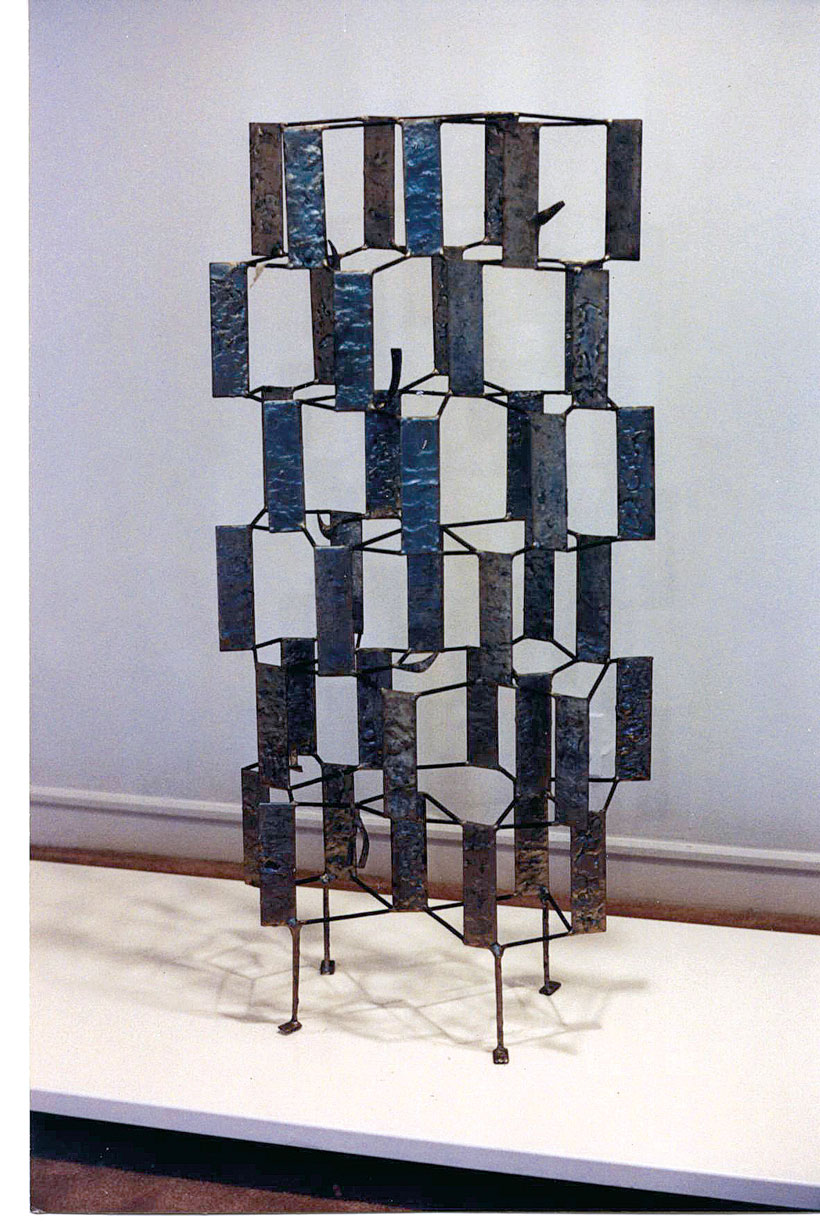

Monotypes

Experimenting with paint rather than metal brought Bertoia to create a vast number of monotypes. “Harry made monotypes with a brayered background, and geometrical shapes stamped on top of the background with shaped wooden blocks,” Celia writes. She also quotes her father as saying, “Drawing on the back side of the page did not permit clear visibility—a great advantage, for it necessitated inner vision to take over the function of the eye.”

These unique pieces of art became a part of Harry’s artistic expression while he was studying at the Cranbrook Academy of Art. About 100 were purchased and featured at the Guggenheim Museum, which started bringing more attention to this newfound talent.

“Harry created the monotypes in solitude, and devised his techniques by himself. As far as he was concerned, he invented the monoprint process of working from the backside of the paper,” Celia writes. He continued crafting monotypes until 1978, although his most prolific era with the form was during the 1940s and 50s.

Jewelry

Harry first toyed with metal jewelry-making in the mid-1930s, and he brought a small box of his work to Cranbrook Academy of Art as part of his application portfolio.

“Much of Harry’s Cranbrook-era jewelry was handcrafted with hammers, pliers and other hand tools. He preferred the surprise and spontaneity achieved with hand tools,” Celia writes.

“The Museum of Modern Art took a bold step with their 1946 exhibition entitled ‘Modern Handmade Jewelry.’ Jewelry, up until that time, usually contained actual jewels, or at least the flowery decorative designs that had been used for centuries,” Celia writes. “This show was one of the first to acknowledge wearable art as a movement in America. The show included 135 pieces of jewelry and intended to bring together the ‘artist as jeweler’ and ‘jeweler as artist.’”

For more on Harry Bertoia, visit harrybertoia.org.

Ready for more inspiration? Meet 4 black designers with amazing Mid Century Modern style.

And of course, don’t forget to follow us on Instagram, Facebook and Pinterest for more Atomic Ranch articles and ideas!