The name Philip Johnson is one that stirs up a mixture of emotions for many fans of modern and postmodern architecture. On one hand, Johnson’s prolific body of works features some truly magnificent structures in a surprising range of styles. On the other, the architect’s life was marred by an ugly political shadow.

Early Life

Philip Johnson was born in 1906 in Cleveland, OH. As a point of interest, his first cousin was architect Theodate Pope Riddle. When he attended Harvard University, he studied philosophy. After graduating, he began spending time in his family’s summer house in Germany. A couple years prior, he’d made the acquaintance of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. This was also the timeframe during which he became interested in Walter Gropius’ and Le Corbusier’s works.

Thanks to a large inheritance, Johnson was able to involve himself with the architectural world. He used the money to launch an architecture department at the Museum of Modern Art, becoming curator. Then he leveraged his growing influence to bring Gropius and Le Corbusier over to visit. He helped set up Mies’ first commission in the US, and eventually helped both him and Marcel Breuer to successfully move to the US from Nazi Germany (where commissions were no longer available).

Involvement with Nazi Germany

Alas, the irony ran deep with Philip Johnson. Given that he helped out Mies and Breuer, it may surprise you to learn that Johnson supported the Nazis.

It would be bad enough if it had been just a “leaning” in their direction. But it was even worse; Johnson was a passionate enthusiast. He excitedly attended a Nuremberg Rally in 1932, and he formed a “Gray Shirts” organization in the US. He even wrote propaganda for the Nazis when they invaded Poland. At one point, the FBI investigated him. Some believe he may even have been a Nazi spy.

As another twist of irony, Johnson was gay. At Nuremberg, he spoke of his admiration of “all those blond boys in black leather.” Apparently, he conveniently ignored Nazi persecution of gay people. Likewise, he seemed to shrug off the professional woes they caused the very colleagues he helped move to the US.

The Glass House

We could spend all day talking about Johnson’s alarming Nazi ties, but we should also discuss his architecture. Thankfully, his attempts to jump into politics and journalism failed. Moving on, he studied under Gropius and Breuer at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, and then began designing modernist buildings.

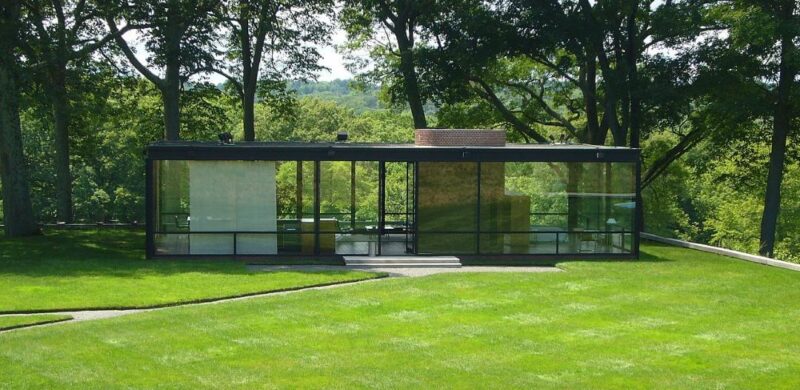

The most famous work by Johnson is undoubtedly the 1949 Glass House, pictured above. Did you notice how much it looks like the Edith Farnsworth House by Mies van der Rohe? The Farnsworth House was its direct inspiration. Van der Rohe, however, did not like it.

Incidentally, even this beautiful structure does not stand entirely apart from Johnson’s fascist views. Disturbingly, his other source of inspiration was a burned-out Polish village.

Of the Glass House, Johnson said, “Storms in this house are horrendous but thrilling. Glass shatters. Danger is one of the greatest things to use in architecture.”

It would seem Johnson liked to live on the edge, whether it was architecturally or politically. Learning Johnson supported the Nazis certainly shatters his image; thankfully, the windows of the Glass House are still standing.

Career

Johnson’s career spanned several distinct periods. First, there was his early modernist period from the 1940s through the 1950s. Then, there was his late modernist period from 1960 through 1980. Following that, he designed postmodern buildings. As a result, there is a lot of diversity in styles between his newer and older buildings. Along with homes, he designed a number of museums, office buildings and other structures.

Did Johnson ever take accountability for his fascist views? Decades later, he did refer to them as “utter, unbelievable stupidity.” But Kazys Varnelis writes in the Journal of Architectural Education, “Johnson makes no apologetic gesture toward his past behavior unless he is confronted by direct questioning, nothing even as paltry as an open letter … At the same time, Johnson continues to promote the same philosophical motives.”

Varnelis points out that Johnson’s motives were largely aesthetic, but “Johnson’s reading of Nietzsche isn’t radically different from the Nazi goal of the aestheticization of the world.” Varnelis adds, “For Johnson, the architect stands as a Nietzschean figure, wielding architecture as the unmediated will-to-power against the masses.”

It’s a fascinating article, and worth a full read if you are looking for a detailed analysis on the ways that Johnson’s beliefs were expressed in his architecture. Ultimately, it is up to each of us individually to decide how (or if) we can balance an appreciation of his talent with distaste for his choices.

If you liked this post, you may also enjoy Take a Tour of Mies van der Rohe’s East Coast Buildings as well as What is the International Style? And of course, don’t forget to follow us on Instagram, Facebook and Pinterest for more Atomic Ranch articles and ideas!