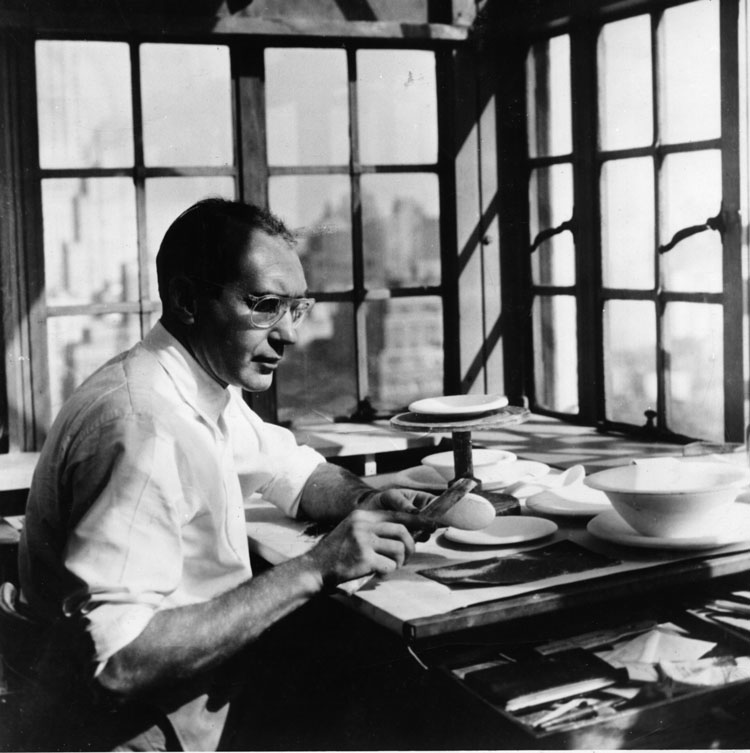

For a designer with as varied an output as Russel Wright, summing up his work in a single object or collection is a difficult challenge. Manitoga, the 75-acre site he conserved in New York’s Hudson Valley and where he built his home, Dragon Rock, comes close to exemplifying Wright’s design aesthetic and philosophy. A stunning site where indoors and out, home and nature effortlessly merge, this was not just the place Wright called home but also his workplace and the ideal showcase for the designer known for creating beautiful, practical and affordable housewares and furnishings, many of which were inspired by nature.

Donald Albrecht is vice president of the board for Manitoga/The Russel Wright Design Center and curator of architecture and designer at the Museum of the City of New York. He’s co-curated exhibits on Wright’s work for the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum and the Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art at the State University of New York in New Paltz, as well as curated exhibits on other midcentury art and design figures including Eero Saarinen and Dorothy Draper. Here, he shares his insights on the lasting impact of Wright’s work and why we should all plan a trip to Manitoga.

Atomic Ranch: What in particular draws you to midcentury figures and designers?

Donald Albrecht: It was a very dynamic, fascinating period in American life and Russel Wright was a major figure during that era who tried to fulfill American ideals of egalitarianism and what he would call “good design for everybody.” With a burgeoning middle class that was occurring after the Second World War, there was an attempt to reach the widest audience, not [products] that just the elite would have but that everybody would be able to enjoy. I find the cultural and social dimensions of the work of these architects and designers like Russel Wright particularly compelling—they’re not just formalists who just make shapes, they actually take part in culture and history.

AR: When did you first discover Wright’s work?

DA: There was a book by William Hennessey [Russel Wright: American Designer, released in 2000] and I remember reading it. Then Wright scholar and collector Robert Schonfeld brought the idea to Cooper Hewitt about doing a Russel Wright show and a book. I co-curated it with him and he then contributed to the book. The Cooper Hewitt museum at that time was particularly interested in [showcasing] these American figures, they had done a show on Henry Dreyfuss, the great industrial designer, and so they were interested in American design and the notions of good design for everybody.

AR: Because Wright did have such a variety of work throughout his career, starting in stage design and architecture and all these different things for the home, and also a little bit of industrial work, how did you go about selecting the pieces that would best represent him in the exhibition?

DA: We focused primarily on the domestic environment, Wright did [design] products for businesses but his real focus was the American home. Especially during the early years of the Depression when people didn’t have a lot of money, he wanted to find a way for people to entertain elegantly and graciously without a lot of cost. He and has wife, Mary Wright, who was in many ways the business genius behind Russel Wright, developed a series of products that could be used in a buffet service and they would say, “You may not have the money for a fancy full sit-down dinner but you can still have an elegant dinner by doing it in a buffet and it will be less expensive,” and they [created] products that fulfill that.

At the end of the Second World War, as many people were moving to suburbia, they addressed that audience and wrote a book called Guide to Easier Living which lays out menu plans, table settings. It shows you new ways of living that were more communal. He did about 11 lines of dinnerware throughout his career, and sometimes it was plastic, sometimes it was ceramic. After the war they did a line called Iroquois, which was dishwasher-proof, because that was one of the new appliances that was being promoted after the Second World War and they wanted to have dinnerware that people could use in the dishwasher, so they were very modern in that way.

[H]e’s a modernist, he’s interested in new materials, but he always knew that the general public wanted some hook back to tradition. If you look at the American Modern dishware, for example, it’s mass-produced but it has glazes that look somewhat handmade. [I]n the early 1930s he created a line of products called Spun Aluminum, he had come to realize that sterling silver and pewter were too expensive for the market he wanted to reach, so went to aluminum. He came to realize, however, that the average person didn’t want the cold, iciness of the aluminum of a hospital bed and so he spun the aluminum, which means he rubbed it with an emery cloth [to give] it the softer finish of pewter. He would advertise it that way, he would say this is inexpensive and it’s modern, it’s aluminum but it has the attributes of the elegance of the past, it has the soft finish or patina of pewter. It also meant that you could mix and match … Russel Wright’s modern pieces and the pieces of the past.

AR: Do you remember your first visit to Manitoga and what that experience was like?

DA: At that time his daughter, Ann Wright, was still living in the house … and I went to interview her in anticipation of [the Cooper Hewitt] exhibition. It’s remarkable, it’s very eccentric, which is ironic given that Russel Wright wanted to appeal to the general audience in his product design but when it came to his own home he created a one-of-a-kind experience. He would argue that the home was a place where you could express your individuality and weren’t supposed to copy his home but you were to take ideas he had presented in his books and his products and you could make your own interpretation of the home, you could do your own thing.

AR: What do you think that fans of his work can learn about him by going to the home as opposed to just having pieces from his collections?

DA: The home can show you how you can live with nature comfortably and in harmony, that was one of his major themes. Also you learn how the home can be a laboratory for your own ideas, how you can take control of your own home and express your personality. You also get a deeper appreciation for somebody. Russel Wright is predominately known for his product designs for the home, that’s what’s in the public mind because that’s what’s seen in museums, it’s what’s offered at auctions, you can buy it on eBay. The fact that he also synthesized product design with architecture, interior design and landscape is something most people don’t know about, and so you will also get a richer experience of this very important American designer.

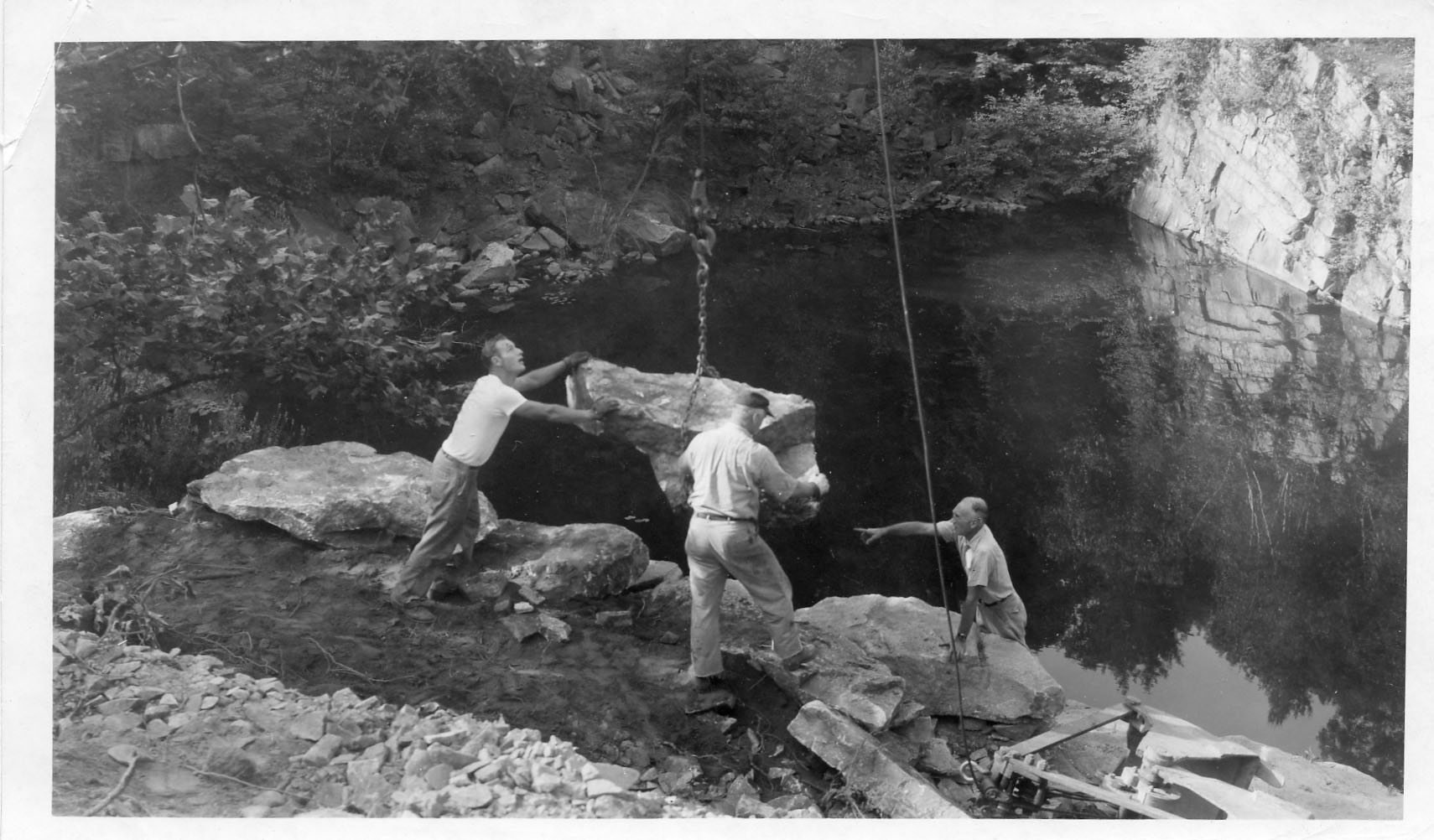

It’s a 75-acre site and he designed it also, he diverted a stream into an old quarry pond [and] made a pool out of it, he carved special trails. He had been a theater designer and while Wright left the theater, the theater never left him, so there’s a very theatrical dimension to the house, it’s very much of a showmanship kind of experience, you’re on a stage in many ways. We do events in which the public sits on the rocks around the quarry pond and you can see how it forms a kind of amphitheater, and this was all created by him. It had been a logging and quarrying site and he converted it into a private residence and a nature preserve.

AR: Why do you think his work continues to resonate so many decades later?

DA: I think it embodies a particular moment in American history, and particularly the late 1940s and into ‘50s and ‘60s, when there was an optimistic, expansionist view of American life, and also the way we can live with nature. One of the things he does, which is quite unusual, he doesn’t cover over the evidence of the former uses of the site, initially it had been a quarrying facility and a logging facility, he leaves evidence of that, so you’ll find throughout the site metal elements that were part of the quarry, which is a very humbling thing to do. He’s letting you know that’s he’s treading lightly on the land and that others had been there before him and he’s not erasing the history of the land, he’s revealing the history of the land. That’s a very environmentally friendly way to do things, he doesn’t bulldoze over the history, he retains the history and then he modifies it and works within it, and we’re trying to do the same thing, we’re trying to also work lightly on the land there.

AR: How are you and the other board members carrying on that preservation work?

DA: [W]e’re now in the process of restoring the landscape. We’ve just developed a relationship with the Open Space Institute and there are now easements that will keep the trails in perpetuity, so if somebody were to buy the property, they could not close the trails to the public. We’re continuing that public access to nature that Russel Wright wanted by making the land more accessible.

At the same time, we’re restoring the house, we’re launching into a big road program that will make access to the house much easier for buses and tours. We’re also picking up on something which Russel Wright himself did, which is to use the house as a showcase for art installations and performances, so every year an artist comes and does an installation at the house and then there’s a concert. People can come and see the house in action, so we’ve picked up on that idea of using the house as a venue for the arts, and [that’s] very popular. [T]he idea of the art installations … goes back to something Russel Wright himself did, so there’s a physical legacy and there’s [also] an intellectual legacy that we’re trying to preserve and advance.

For more information on Manitoga/The Russel Wright Design Center, visit visitmanitoga.org.