Brutalist architecture, or Brutalism, well known for its imposing features and grim representation in spy thrillers and science fiction films, is one of the most debated architectural styles to appear in blueprint. Some celebrate it as innovative and practical. Others, such as Charles III, then Prince of Wales, find “piles of concrete” a more suitable description. Many rejected it due to its common association with socialist ideologies, as many Brutalist architects advocated for socialist ideology.

“Brutalism” emerged in the mid-20th century as a tongue-in-cheek term by architect Hans Asplund to describe the work of his predecessors, Bengt Edman and Lennart Holm. The two architects had designed a brick building in Uppsala, Sweden that had no hint of charm—a simple rectangular brick building with a few windows.

Asplund used ‘Brutalism’ as a double-reference to the French term béton brut (“raw concrete”) and the disdain many elite architect critics experienced when they found themselves confronted by the building.

One Brutalist product, the 1972 Trellick Tower in London, has even been coined the “Tower of Terror” because of its 332 feet of gloomy aesthetic and reputation as a crime-nest. But is that all there is to Brutalism—concrete and suspicion?

Some architectural styles value form over function, others combine the two; but Brutalism submits to the will of the function. It prides itself on exposing buildings’ functions. Its style is most commonly seen in public buildings, such as public housing, libraries and government institutions. While the character of Brutalism is intimidating, the key to understanding its logic is hidden within it’s architecture.

Here are five main characteristics of Brutalism, deconstructed:

Block Structures

The Habitat 67 in Montreal, designed by Moshe Sadie in 1967, is perhaps the best example of Brutalism’s block structures. 354 stacked concrete units form a modern day haven from traditional apartment complexes. Geometric, interlocked block formations drew attention by offering equal living spaces (part of why it’s commonly associated with socialist ideology) and affordable rent for incoming tenants.

Unfinished Concrete

If it’s not brick, it will almost certainly be unfinished concrete (concrete that is left alone after being cast instead of receiving finishing treatments to smooth out lines and blemishes). This leaves different impressions. The resulting concrete may be naturally smooth or the casting process might leave behind wood patterns from board shuttering. Brutalism sees no need to accessorize the skeleton of a building; it chooses to find beauty in beginnings rather than finales.

Cost-effective

Brutalism’s popularity rose primarily in the years after World War II because of its cost effectiveness. Due to considerable destruction in so many cities, governments couldn’t afford the ornate details on all their public buildings. Thus, they made lemonade out of lemons and forwent the sugar. Brutalism’s ability to bypass expensive finishing touches made it a popular choice for patrons who wanted to rebuild quickly without deepening financial burdens.

Exposed Utilities

Brutalism celebrates authenticity. Water tanks, support elements and electrical towers are left visible instead of concealed behind closed doors. The “Mouse Bunker,” designed by Gerd Hanska, in Berlin is an excellent example. Pipes protrude through the exterior walls like cannons on a ship and the electrical systems can be seen on top.

Funny enough, the Mouse Bunker was intended to be a cheap build—originally projected to cost $4 million; however, the bill had skyrocketed to $126 million by the time it opened in 1982. In case you’re wondering why this enormous building was dubbed the Mouse Bunker, the nickname came from its use as an animal testing facility.

Symmetry and Asymmetry

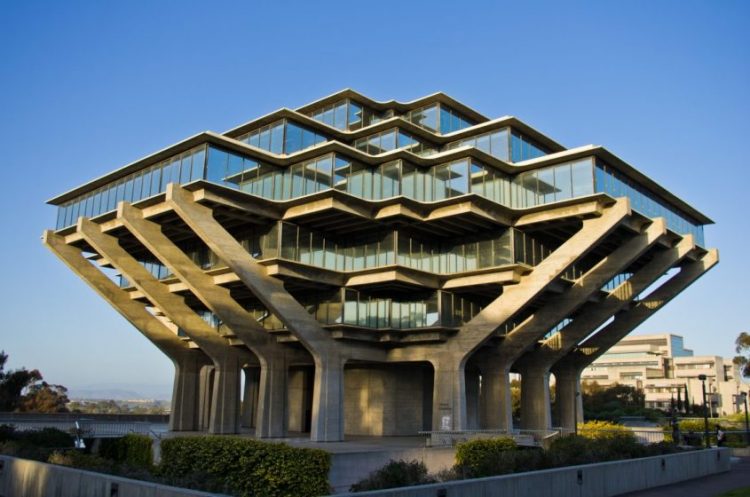

Brutalism is not a picky eater; it embraces both symmetry and asymmetry. The Geisel Library, designed by William Pereira in San Diego, 1970, speaks to the remarkable symmetry found in brutalist architecture. The angled support pillars topped by the sharp peaks of a crowning summit refuse to be anything less than mesmerizing.

It’s challenger: Janko Kostantinov’s post office and telecommunications center in Macedonia, finished in 1981. The funky building reaches ahead of its time with asymmetrical curves.

Brutalist architecture and design is currently experiencing a renaissance of renewed appreciation. In an era when many Modernist buildings are being demolished, the raw beauty of Brutalist design has attracted a new generation of enthusiasts, giving hope for the style’s survival.

For more instances of Brutalism, don’t miss our latest fall issue! You can also stop by and discover the often controversial history and design of Brutalist buildings such as Lauinger Library: A Brutalist Take on Romanesque Design, 33 Thomas Street: A Sleek Brutalist Habitat for Machines and Boston City Hall: A Controversial Brutalist Landmark.

For more instances of Brutalism, don’t miss our latest fall issue! You can also stop by and discover the often controversial history and design of Brutalist buildings such as Lauinger Library: A Brutalist Take on Romanesque Design, 33 Thomas Street: A Sleek Brutalist Habitat for Machines and Boston City Hall: A Controversial Brutalist Landmark.

And of course, don’t forget to follow us on Instagram, Facebook and Pinterest for more mid century articles and ideas!